Continue reading “PILs/ Social Action Litigation in H.P High Court”

Category: Uncategorized

Law regarding Groundwater

INTRODUCTION

Groundwater use in India has increased tremendously over the last few decades. It has become the most important source of freshwater for almost all *46 uses. It has been estimated that around 60 per cent of the irrigated agriculture depends upon groundwater and more than 80 per cent of drinking water needs are met by groundwater.2 Continue reading “Law regarding Groundwater”

Forest rights – CHANGING TERRAIN OF ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA’S FORESTS

INTRODUCTION

Girish Kasaravalli’s movie ‘Dweepa’ or ‘the Island’ showcases the narrative of a family that refuses to leave an island despite the construction of a dam. In a scene, the protagonist is seen negotiating for compensation for the loss of the sacred temple that his family has been serving in for generations. The compensation officer dismisses the claim on the basis that the family does not have documentation of ownership Continue reading “Forest rights – CHANGING TERRAIN OF ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA’S FORESTS”

Social justice bench- remembering J. Lokur

In Ashwani Kumar v. Union of India, WP (C) No. 193 of 2016, J. Lokur directed the Government to ensure that elderly people’s rights under Article 21 are properly enforced. In his opening statement, Justice Lokur reiterated his position in these terms: Continue reading “Social justice bench- remembering J. Lokur”

Legalising “Medical Cannabis” & “Industrial hemp” in Himalayas. — Part 1

The unawareness and lack of education regarding the difference between hemp and recreational cannabis and the political link between the two, is impeding Himachal Pradesh’s ability to cash in on the biggest upcoming industries around cannabis in the world. Hemp cultivation has become green gold in countries like China and the United States of America. Continue reading “Legalising “Medical Cannabis” & “Industrial hemp” in Himalayas. — Part 1”

Whether “DPC” is required to be guided merely by the overall grading or can it make its own assessment on the basis of the entries/“remarks in the ACRs “and other relevant material

DPC enjoys full discretion to devise its own methods and procedure for objective assessment of the suitability of the candidates. It has been understood by the Hon’ble Apex court in plethora of cases that DPC should not be guided merely by the overall grading that may be recorded in the confidential report Continue reading “Whether “DPC” is required to be guided merely by the overall grading or can it make its own assessment on the basis of the entries/“remarks in the ACRs “and other relevant material”

What is the scope of judicial review of the assessment arrived at by the DPC ?

The Hon’ble Supreme Court has stated in various cases that the decision of the Selection Committee can be interfered with only on limited grounds by the process of judicial review, these limited grounds are: Continue reading “What is the scope of judicial review of the assessment arrived at by the DPC ?”

Wheather the effect of the judgment can be undone by bringing out amendments in law

In the Indian constitutional framework, the Legislature, Executive, and Judiciary are the three organs of State power, each with clearly demarcated spheres of functioning. While Parliament and State Legislatures make laws, the Judiciary interprets and applies them. However, when a court strikes down a law or grants relief on the interpretation of a statute, can the Legislature intervene and undo the effect of such judgment?

This legal conundrum finds its answer in the principle of “changing the basis” of law—a nuanced doctrine that permits legislative override only when it alters the factual or legal substratum that formed the foundation of a court’s decision.

This article analyses the scope, limits, and constitutional boundaries of this principle through landmark judgments of the Supreme Court and the evolving jurisprudence on the separation of powers.

II. The Doctrine of “Changing the Basis” of Law: Meaning and Scope

The doctrine allows the Legislature to respond to judicial decisions by:

- Removing the defect in the law identified by the court, and

- Altering the legal or factual basis that led to the judicial decision.

Critically, the Legislature cannot simply declare a judgment void or incorrect—that would amount to exercising judicial power, which is impermissible.

As held in Shri Prithvi Cotton Mills Ltd. v. Broach Borough Municipality, (1969) 2 SCC 283:

“A court’s decision must always bind unless the conditions on which it is based are so fundamentally altered that the decision could not have been given in the altered circumstances.”

Thus, legislation that retrospectively changes the law’s basis can validly affect pending or future claims but cannot negate a final decision inter partes unless the altered law renders such relief untenable.

III. Judicial Clarifications: Key Cases and Detailed Analysis

1. Shri Prithvi Cotton Mills Ltd. v. Broach Borough Municipality, (1969) 2 SCC 283

In this seminal case, the Municipality had levied a cess on the appellants, which was quashed by the High Court. The Legislature thereafter enacted a validation law making the cess retrospectively valid.

Held:

The Supreme Court upheld the legislation, stating that the Legislature could remove the defect retrospectively and validate levies. However, the Legislature cannot merely say that a judicial decision shall not bind.

Key takeaway: Legislative override is valid if it removes the basis of the judgment and does not directly invalidate the judicial outcome.

2. Indian Aluminium Co. v. State of Kerala, (1996) 7 SCC 637

The Kerala High Court struck down certain imposts. The State amended the Kerala Electricity Duty Act retrospectively.

Held:

The Supreme Court upheld the amendment, observing that the new legislation cured the defect identified by the Court and applied uniformly to all similarly situated parties.

3. Cauvery Water Disputes Tribunal, Re, 1993 Supp (1) SCC 96

This Constitution Bench decision reiterated that while the Legislature may change the general basis of a judgment, it cannot nullify an individual adjudication.

“It is permissible to change the law retrospectively, thereby affecting future cases. But it is not permissible to legislate to reverse a judicial determination between specific parties.”

4. W.S.R. Bhagwat v. State of Mysore, (1995) 6 SCC 16

-

Legislative Overreach:The State of Mysore attempted to circumvent a final High Court judgment by enacting a law that effectively nullified the court’s decision on seniority and promotions for certain employees.

-

Judicial Supremacy:The Supreme Court, in this case, reaffirmed the principle that legislative bodies cannot override final judicial decisions, especially those concerning fundamental rights and established legal principles.

-

Impact of the Decision:The court’s decision in Bhagwat v. State of Mysore has significant implications for the separation of powers and the protection of individual rights. It reinforces the idea that judicial decisions, once final, must be respected and implemented by all branches of government.

-

Reading Down Provisions:The court did not only strike down one section of the law but also read down other problematic provisions. This means the court interpreted those provisions in a way that aligned with constitutional principles and the High Court’s judgment.

-

Consequences for the State:The State of Mysore was directed to comply with the High Court’s original directions, including providing consequential financial benefits to the affected employees.

5. State of Tamil Nadu v. State of Kerala, (2014) 12 SCC 696

This Constitution Bench crystallized the limits of legislative override of judgments:

- Legislature cannot render judgments void or ineffective;

- It can, however, alter the statutory conditions upon which the judgment was based;

- Separation of powers is part of the basic structure of the Constitution;

- Judicial pronouncements cannot be annulled by legislative fiat.

This case has become the touchstone for analyzing legislative conduct post-judgment.

6. Cheviti Venkanna Yadav v. State of Telangana, (2017) 1 SCC 283

7. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd. v. State of Bihar, (1990) 4 SCC 557

This decision upheld the validity of a law which sought to impose cess retrospectively. The Court noted that the Legislature had removed the infirmity, thus passing the test laid down in Prithvi Cotton Mills.

8. Indian Aluminium Co. Ltd. v. State of Kerala, (1996) 7 SCC 637

This case is frequently cited as an illustration of how validation laws can remove the basis of a judgment and survive judicial scrutiny, provided they operate on a general class and not to nullify individual relief.

IV. Contemporary Applications and Examples

A. Vodafone Case and Retrospective Taxation

In Vodafone International Holdings BV v. Union of India (2012) 6 SCC 613, the Supreme Court held that capital gains tax did not apply to offshore indirect transfers. Parliament responded with retrospective amendments to Section 9 of the Income Tax Act.

The government later withdrew the demand in 2021, acknowledging the controversy, but it remains a powerful example of Parliament’s ability to change the basis of a ruling—even if politically unpopular.

B. Reservation Policies

Several State laws expanding reservation percentages were enacted after the Supreme Court’s ceiling in Indra Sawhney v. Union of India, 1992 Supp (3) SCC 217. Attempts to insert reservations beyond 50% through constitutional amendments (e.g., Maratha reservation and the 103rd Amendment) have tested the waters of judicial override via constitutional means, some of which are still under judicial scrutiny.

V. What Legislature Can and Cannot Do

| Permissible | Impermissible |

|---|---|

| Change legal basis of a judgment | Declare a judgment void or wrong |

| Enact validation laws to cure defects | Legislate to reverse relief granted inter partes |

| Retrospective application to classes | Selective denial of benefit to litigants alone |

| Amend laws post-judgment with uniform applicability | Encroach into judicial functions by overruling findings |

VI. Doctrine of Mandamus and Limits on Legislative Response

A mandamus issued by a High Court or Supreme Court is a judicial command enforceable under Article 226 or 32. The Legislature cannot nullify it by statute, unless the legal basis of the mandamus itself is changed. The Judiciary retains the power to enforce its directives against the State.

VII. Conclusion

The doctrine of changing the basis of law reflects a constitutional compromise between the supremacy of Parliament in legislative affairs and the independence of the Judiciary in interpreting laws.

It allows the Legislature to legitimately respond to judicial findings by curing defects, amending the legal landscape, and ensuring that law evolves. However, it draws a red line at judicial finality, which cannot be disturbed without offending the doctrine of separation of powers, a part of the basic structure of the Constitution.

The judicial decisions discussed above provide not only boundaries for legislative action but also guideposts for maintaining a harmonious constitutional balance.

Jurisdiction of electricity tribunal

STATUTORY PROVISION

THE ELECTRICITY ACT, 2003 [No.36 of 2003]

Intention of the legislature- An Act to consolidate the laws relating to generation, transmission, distribution, trading and use of electricity and generally for taking measures conducive to development of electricity industry, promoting competition therein, protecting interest of consumers and supply of electricity to all areas, Continue reading “Jurisdiction of electricity tribunal”

Defacement of Himalayas ~A Call to Tackle Visual Pollution

Preserving Shimla’s Pristine Beauty: A Call to Tackle Visual Pollution

Shimla, nestled in the embrace of the mighty Himalayas, is a natural paradise adorned with lush forests, babbling streams, meadows, and pristine lakes. This breathtaking haven, often referred to as the “Abode of the Gods,” offers respite from the scorching plains and beckons adventure enthusiasts with its trekking trails, jeep safaris, paragliding, and river rafting. However, amidst its natural splendor, Shimla grapples with an increasingly pressing issue – visual pollution.

Shimla: A Glimpse

Situated at an elevation of 7200 feet in the north-western Himalayas, Shimla is not just a picturesque destination but also the capital of Himachal Pradesh. Its landscape is draped in dense oak and pine forests, rhododendron blooms, and a captivating colonial legacy. The town boasts splendid colonial edifices, charming cottages, and enchanting walks.

Shimla’s rich history is intertwined with its transformation into the summer capital of British India during the Raj. While the colonial era has passed, its architectural legacy endures. Notable landmarks include the Viceregal Lodge, gaiety theatre, and the former imperial Civil Secretariat. These architectural treasures offer a glimpse into India’s past when one-fifth of humanity was governed from Shimla.

The town sprawls across Seven Hills, each adorned with lush meadows and pine forests. Prospect, Observatory, Elysium, Jakhoo, Strawberry, Summerhill, and Inverarm – these hills create a stunning backdrop for Shimla’s unique charm.

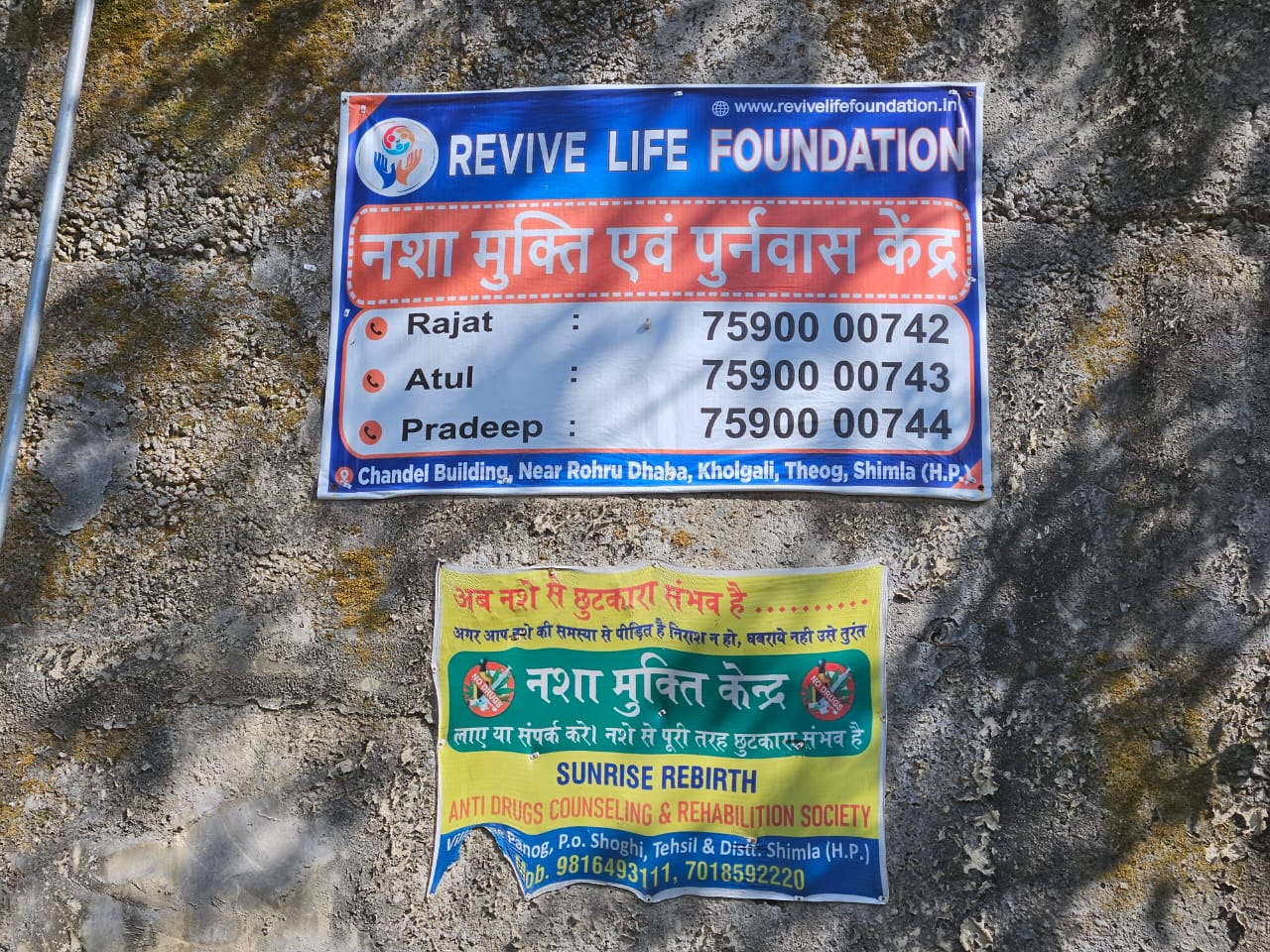

The Growing Issue of Visual Pollution

While Shimla’s natural beauty is unparalleled, a growing menace threatens its aesthetic appeal – visual pollution. During election seasons, the cityscape becomes cluttered with political posters, billboards, and slogans. These visuals mar the town’s natural aesthetics and architectural splendor.

The problem isn’t limited to electioneering. Advertisements for educational institutions, movie promotions, and other commercial ventures also contribute to this unsightly visual clutter. Posters and hoardings are plastered across walls, buildings, and even trees, diminishing Shimla’s natural beauty.

Reports suggest that some political parties even engage painters to conduct a wall-writing campaign, disregarding legal prohibitions. Writing on government and public properties without permission is not just an eyesore but also a violation of the law.

The Environmental Impact

The consequences of visual pollution extend beyond aesthetics. It hampers Shimla’s ongoing beautification projects and obstructs public roads and traffic. Moreover, the materials used in these advertisements, often non-biodegradable, contribute to environmental damage if not disposed of properly.

State authorities have invested over 100 crore rupees in beautification initiatives for Shimla. However, the continuous defacement of public property undermines these efforts. The public, tourists, and the environment suffer from this degradation.

The Deteriorating Election Culture

The issue of visual pollution is closely linked to the deteriorating election culture in Himachal Pradesh. The past 15 years have witnessed a downward spiral in electioneering behavior. This includes tearing down opponents’ campaign posters and widespread illegal posting of banners, hoardings, and posters.

These activities cause public nuisance and violate citizens’ fundamental rights, including those guaranteed by Article 21 of the Indian Constitution. These visual eyesores compromise the right to a clean and beautiful environment.

A Call for Change

Preserving Shimla’s pristine beauty and restoring its splendor is not just a responsibility but a collective duty. The authorities must adopt a zero-tolerance approach to visual pollution, which includes:

- Prohibiting the sticking and pasting of advertisements on walls and buildings.

- Preventing the hanging of advertisements from trees.

- Strict enforcement against paintings on rocks and walls without permission.

- Promoting the use of biodegradable materials in bills, banners, stickers, and posters.

The Division Bench of the Hon’ble High Court of Himachal Pradesh in CWP 2312 of 2017, Order Dated 16/10/2017 stated the following;

- Mr. Devan Khanna invites our attention to the decisions rendered by Hon’ble the Apex Court in:(a) N.K. Bajpai v. Union India, (2012) 4 SCC 653;(b) M.P. v. Kedia Leather & Liquor Ltd., (2003) 7 SCC 389;(c) Chameli Singh v. State of U.P., (1996) 2 SCC 549;as well as the provisions of the Himachal Pradesh Open Places (Prevention of Disfigurement) Act, 1985 (hereinafter referred to as the Act).

- Primarily, the issue pertains to the manner in which the political parties indulge in wall writing and setting up of hoardings, in gross violation of the provisions of the Act, as also the Model Code of Conduct and the Environmental Laws of the land.Public places and places open to public view stand defined in Section 2 of the Act, which reads as under:

- (a) “advertisement” means any printed, cyclostyled, typed or written notice, document, paper, or any other thing containing any letter, word, picture, sign, or visible representation;

- (b) “places open to public view” include any private place or building, monument, statue, post, wall, fence, tree, or contrivance visible to a person being in, or passing along, any public place;

- (c) “public place” means any place (including a road, street, or way, whether a thoroughfare or not and landing place) to which the public are granted access or have a right to resort or over which they have a right to pass.

- Significantly, “advertisement” includes any printed, cyclostyled, typed, or written notice, document, paper, or any other thing containing any letter, word, picture, sign, or visible representation. The definition is inclusive. Such advertisement is prohibited to be exhibited, both at “places open to public view” and “public places”, unless so ordered otherwise. Action contrary to the statute is penal in nature, and the burden, in terms of Section 4 of the Act, to establish innocence is on the offender.

- Even offenses by companies are covered under Section 6 of the Act. “Company” again has been defined to also include an association of individuals, which in our considered view, would cover political parties.

- Mr. Devan Khanna also invites our attention to various circulars issued by the Election Commission of India from time to time.

- Noticeably, these days banners for advertisement are not made of cloth but of non-biodegradable material, which further aggravates the environmental pollution.

- Under these circumstances, by way of interim, we direct that the Himachal Pradesh Chief Electoral Officer – respondent No.6 shall issue appropriate directions to all the District Election Officers/Returning Officers, who are involved in the conduct of elections to the Himachal Pradesh State Legislative Assembly to be held on 9.11.2017, to the following effect:

- “No wall writing, pasting of posters/papers or defacement in any other form, or erecting/displaying of cutouts, hoardings, banners flags etc. shall be permitted on any Government premise (including civil structures therein). For this purpose a Government premise would include any Govt. office and the campus wherein the office building is situated;

- Wall writing, pasting of posters, and similar other permanent/semi-permanent defacement which is not easily removable, shall not be resorted to on any “public places” and “places open to public view” under any circumstances even on the pretext of the consent of the owner of the property, except in accordance with law. wall writing, pasting of posters, and similar other permanent/semi-permanent defacement which is not easily removable, shall not be resorted to on any “public places” and “places open to public view” under any circumstances even on the pretext of the consent of the owner of the property, except in accordance with law.

It’s time to reclaim Shimla’s visual aesthetics and protect the rights of its residents and visitors to enjoy a clean and beautiful environment. The future of Shimla depends on the actions we take today to combat visual pollution, restore its pristine charm, and uphold its legacy as the “Queen of Hills.”

High Court’s gift to the daughters of freedom fighters on Independence Day- Gender Discrimination

(The Court on 14 August 2018 struck down a 1984 policy of the State which discriminated against the married daughters of freedom fighters . The policy did not consider the married women at par with the married sons and specifically Continue reading “High Court’s gift to the daughters of freedom fighters on Independence Day- Gender Discrimination”

Free Speech and Contempt of Court

On May 31, the Times of India reported some observations of a two-judge bench of the Supreme Court on its contempt powers. The Court noted that the power to punish for contempt was necessary to “secure public respect and confidence in the judicial process”, and also went on to add – rather absurdly – to lay down the requirements, in terms of timing, tone and tenor, of a truly “contrite” apology.This opinion, however, provides us with a good opportunity to examine one of the most under-theorised aspects of Indian free speech law: the contempt power.