INTRODUCTION

Girish Kasaravalli’s movie ‘Dweepa’ or ‘the Island’ showcases the narrative of a family that refuses to leave an island despite the construction of a dam. In a scene, the protagonist is seen negotiating for compensation for the loss of the sacred temple that his family has been serving in for generations. The compensation officer dismisses the claim on the basis that the family does not have documentation of ownership and the protagonist is seen walking away in anger where he says that the forest, the village and the temples are theirs – what then is this this skewed idea that the state is the owner of public property. This scene illustrates the ongoing struggle within India for the rights over resources, particularly in forest areas. This conflict with the officer is a conflict over the competing meanings of ownership, control and property rights over nature. This conflict is at the heart of environmental justice movements in forest areas where local communities are seen struggling for their rights over jal, jangal and zameen (water, forest and land).

In this paper I will locate the notion of environmental citizenship derived from a schematic study of the struggles by forest dwelling communities in India’s forests. I contrast this meaning of environmental citizenship with the understanding of environmental citizenship from literature in the global south where similar struggles have occurred. In the present section I also draw on the relationship between environmental citizenship and law in India. While exploring this relationship between environmental citizenship and law, I speak about the process where the tenets of environmental citizenship derived from forest rights struggles have been infused into law. I then contrast this notion of environmental citizenship with corporate citizenship to highlight the relationship between corporations, the environment and democracy. In doing so I set the frame through which I examine three changes to the existing environmental legal framework proposed by the present government where it has reduced the participation of forest dwelling communities in the decision making whilst increasing the power of corporations to self-regulate. I conclude with an analysis of these changes on the environmental citizenship of forest dwelling communities. This paper is an attempt to explore environmental citizenship as a normative concept that has seeped into law through the discourse that has emerged from environmental movements. As a normative concept it guides democratizes decision-making around the environment and it is the movement away from this form of environmental citizenship that is being proposed by the recent changes to environmental laws that this paper highlights. Environmental citizenship and its tenets elaborated below act as an aspirational standard for guiding environmental law amendments and jurisprudence. The paper also aims to provide a schematic discussion of how citizenship becomes the terrain on which rights and control over natural resources is being contested. This builds on the existing work by eminent scholars like Ramchandra Guha and others who address these contestations but this paper seeks to incorporate the legal dimension to how these contestations play out.

Environmental justice movements in India have followed the paradigm of ecological concerns merging with questions of equity. Ramchandra Guha in his seminal work titled Radical American Environmentalism and Wilderness Preservation- A Third World Critique critiqued the deep ecology movement in the global north which alludes to the need for pristine areas without human interference and raised the question of the plight of resource dependent communities.2 This came to be known as the environmentalism of the poor, where the concerns of ecology and conservation needed to be examined through the lens of social justice considerations. The history of environmental justice movements in forest areas is rife with the contestations over resources and their prospective use. Political ecology informed these movements that if rights to forest dwelling communities were granted then ecological questions would also be addressed. In the same vein Ramchandra Guha further speaks about how environmental justice movements are driven by the idea of alternative sustainable use of nature in contrast to more destructive practices.3 This fight for control over resources is also one of historical injustice. Historical injustice here refers to the systematic loss of control over resources that forest dwelling communities have been subjected to since the colonial encounter. A brief examination of forest laws shows that independent India inherited the colonial framework of exclusionary conservation and prohibited resource use in protected areas. This legal framework criminalized the resource use of forest dwelling communities who have been living in these areas and using these resources for generations. This dimension of the conflict where the law delegitimized the biocultural linkages of the local communities to their resources was viewed by these communities as a process of state appropriation. Eminent domain is a principle where the State is the eventual owner or arbiter for the use of resources reasserted state control over resources.

In this milieu, the relationship of forest dwelling communities with the state was shaped by resistance movements to gain control over resources in most *77 parts. In other forest areas impacted by the Naxal movement,4 this relationship was also fraught with questions of illegal arrests of adivasis on false charges. The relationship of forest dwelling communities with the state is a complex one riddled with questions of oppression, subjugation and resistance. For the purposes of this paper I am keen on unpacking this relationship to the extent that it deals with the legal constructs of ownership, control and rights over resources. In this context the relationship between forest dwelling communities and the state5 is determined by many competing legal constructs for ownership, control and rights over resources in forest areas. The dominant constructs that configure this relationship are the doctrine of eminent domain6 as articulated in the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013; public trust doctrine7 as understood in M.C Mehta v. Kamal Nath 1996 Indlaw SC 1476; 8 Schedule V areas; The Wildlife Protection Act, 1972; Forest Conservation Act, 1980; and the passing of the Forest Rights Act, 2006 (FRA). In the table below I provide a simplistic breakdown of these laws and how they shape the notions of ownership, control and rights in forest areas.

LAW or DOCTRINE

STATE CONTROL

RIGHTS OF FOREST DWELLING COMMUNITIES

Doctrine of Eminent Domain

State has the power to divert forest land for public purpose.

Rights of communities are restricted to compensation and rehabilitation.

Public Trust Doctrine

State holds the resources in trust and thus has the duty to protect these resources.

Communities have the right to public enjoyment and common heritage to these resources.

Scheduled Areas

State surrenders ownership and control to scheduled tribes. These areas include forests.

Scheduled tribe communities have complete ownership, control and rights over resources though this is limited to surface rights and does not extend to rights to minerals below

State has the ability to declare forest areas as protected areas ranging national parks, sanctuaries to tiger reserves.

Communities have restricted rights of access and use of forest resources.

The center grants clearance or permission for the use of forest land for a non –forest purpose.

Community consent is not a part of this process.

Forest Rights Act,2006

State control over forest areas is restricted by shifting ownership and control to forest dwelling communities.

Community control over forest areas is enshrined through forest rights recognized within the FRA.

As seen in the table above, the contestation over natural resources is also represented within the legal framework with some laws reasserting the power of the state and other laws calling for a radical shift of control to local communities.

Another dimension of this conflict is the expression of private corporate interests over natural resources which compromise interests of local communities. The State is the arbiter of negotiating these interests through the legal constructs mentioned earlier as well as the environment impact assessment process which is a part of the Environment Protection Act, 1986. The environment impact assessment (‘EIA’) process requires that the project proponent divulge the environmental impact of the proposed development project and in the case of site-specific projects like mining, it is mandatory for the project proponent to undertake site-specific clearances. An element where *79 local communities articulate their interests is in the public hearing process which is a part of the larger EIA process. What is important to note is that in this process the local communities are consulted but their consent need not be obtained.9 There was a shift from the language of consultation to consent with the passing of the FRA where the consent of the gram sabha was to be taken for development projects within forest areas. It is this relationship between the state, the forest dwelling communities and private and public corporations that I intend to explore through the framework of environmental citizenship which is an emerging concept in social sciences. In the next section I will elaborate on the notion of environmental citizenship and the role of environmental law in shaping its contours in India.

II. ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP AND LAW IN INDIA

Environmental citizenship as a concept is yet to be explicitly explored in India though most scholarship around environmental justice issues implicitly alludes to contestations over nature as one of citizenship. Environmental citizenship is seen as an extension of the broader discourse around citizenship in western philosophy. A number of writers have noted three dimensions of citizenship, although they characterize them in slightly different terms. The first, which we call the legal dimension, centers on the formal status of the citizen, defined by civil, social, and political rights, and considers the scope of personal autonomy and freedom of expression, as well as other freedoms that the law accords the individual. The second, the procedural dimension, addresses the formulation of the law and other political institutions and considers the role of the citizen in shaping them, particularly through direct participation and through representative democracy in different forms and at different scales. The third, the identity dimension, examines the sense of membership in the collectivity itself; it addresses questions of citizenship as identity and the struggle for the incorporation within the collectivity.10 The three dimensions of citizenship mentioned can be reduced to the relationship between the state and its citizens through rights, direct participation and inclusion. These are the tenets and the language used in the desire of forest dwelling communities to be a part of decision making around natural resources. I chose to use the frame of environmental citizenship in articulating the complex changes in our environmental laws because it enables us to link the politics of nature with the question of democracy and justice. I also view citizenship as a terrain on which rights are negotiated and revised through the different institutional structures. Environmental citizenship is a way to incorporate environmental considerations within the discourse of citizenship claims. It reshapes the discourse in a way that is more acutely political and more integrally ecological.11

Environmental citizenship when examined through the lens of environmental justice movements in India is one driven by the values of decentralization of ownership and control, and democratization and participation of forest dwelling communities in the decision-making processes. These values found their way into law through the Forest Rights Act, 2006. The FRA enshrines forest dwelling communities with rights over forest land and the right to manage and control community forest areas, this assures decentralized control of resources and active participation of local communities in conservation efforts. However, the link between the environment and citizenship is not restricted to forest dwelling communities but extends to private corporations, urban middle class and other stakeholders.

What then is the notion or tenets of environmental citizenship when seen through the different dimensions of citizenship as laid down by Beland and Hansen12 as the legal, procedural and identity based dimensions? In the legal dimension it refers to the formal status of citizenship through what I describe as environmental rights and obligations. The procedural dimension refers to direct participation in environmental decision making and identity, which is a contentious aspect of environmental citizenship in India. In the table below I have elaborated on the three dimensions of citizenship as derived from the laws which were products of the environmental justice movements in India.*81

DIMENSIONS OF CITIZENSHIP

FOREST DWELLING COMMUNITIES

LEGAL

Forest dwelling communities have rights of use, ownership of forest land and control over the management of forest areas under the FRA. These rights are subject to the responsibility to conserve the environment. These are rights beyond the basic rights of freedom o f expression and other fundamental rights.

PROCEDURAL

Consent of forest dwelling communities needs to be obtained for any development activity that is to take place within forest areas. They directly participate in the decision making around the strategies to conserve the forests.

IDENTITY

Scheduled tribes are granted these rights by virtue of being scheduled while other forest dwelling communities namely Dalit forest dwellers and pastoral community members are required to provide evidence of having inhabited forest areas for 75 years This aspect of environmental citizenship of forest dwelling communities is yet to be developed and addressed.

These neat boxes are not an exhaustive understanding of environmental citizenship of forest dwelling communities, nor are they watertight. The three dimensions work collaboratively to enable the realization of environmental citizenship of forest dwelling communities. As noticed, there is a strong legal discourse around environmental rights to forest dwelling communities, direct participation and identity based inclusion and exclusion to these rights. Environmental citizenship is dynamic and can be viewed as a site of struggle where its different dimensions are negotiated. The legislative process is *82 intercepted by inclusion of movements in the drafting of laws like the FRA while at the same time direct participation is prevented through negligent implementation of public hearing processes. Holston speaks of the transformative potential of citizen movements from below. His concept of ‘insurgent citizens’ speaks to the agency of popular movements to impact decision making in the environment sphere.13 Extending this idea of the insurgent citizen, environmental citizenship in India is unique in that exercises of citizen insurgency have transformed legislative intent and jurisprudence. Environmental citizenship in India’s forests has been moved forward from insurgent practices of protests for ownership, control and rights over forest areas. This can be seen particularly with the passing of the FRA where the movement for rights in forest areas resulted in the passage of the law. Another instance is the broad interpretation of the scheduled area provisions in the constitution in the Samatha judgment.14 The legislature and the judiciary have, at critical junctures, been receptive to the insurgent citizenship practices of forest dwelling communities through different public interest litigation cases filed before the courts and requests for amending existing laws. Environmental movements have used law as a tool of resistance, this has been in the form of filing cases before the courts to campaigning for legislative action. An example that illustrates the ability of insurgent citizenship practices that have resulted in change is the Vedanta judgement15 passed by the Supreme Court. This landmark judgement extended the powers of the gram sabha within the FRA to require consent for the development project. This judgement came in the backdrop of ongoing protests by Dongria Kondh community members claiming their rights over their sacred space. This legal claim of assertion of rights over the Niyamgiri Hill as a sacred site produced jurisprudence where such a right came to be recognised and protected. The insurgent citizenship practice of inserting a legal claim within the social movement has resulted in responses from the judiciary and legislature. However, there are several instances where the law has failed to respond to the legal claims being made by insurgent citizenship practices of protest and legal activism. An instance of that is the Supreme Court’s response *83 to the cases filed against the construction of dams within the Narmada Valley Project. The Supreme Court when interpreting the precautionary principle stated the following:

In present case, we are not concerned with polluting industry…what is being constructed is a large dam. The dam is neither a nuclear establishment nor a polluting industry. The construction of a dam undoubtedly would result in the change of environment but it will not be correct to presume that the construction of a large dam like SardarSarovar will result in ecological disaster. ….The experience does not show that construction of a dam … leads to ecological or environmental degradation.

The relationship between assertion of environmental citizenship and the law is fraught with recognition of rights claimed by communities adversely impacted by development projects or the complete denial of such rights. Thus insurgent citizenship has transformed environmental jurisprudence whilst also at times restricting the interpretation of such rights claims.

In a song inspired by Bhagwan Maaji leader of the Adivasi struggle against bauxite mining called ‘We will not leave our village’ elaborates on the resistance based citizenship claims made by forest dwelling communities. It begins with the following lines

We will not leave our village,

We will not leave our forests,

We will not leave our mother-earth,

We will not stop our struggle.16

This is a narrative of environmental citizenship where the claim for ownership and control is based on the stewardship of the earth. It is distrust of the state as the trustee of resources as forest dwelling communities have witnessed the loss of land and forest to commercial interests and seek to act as trustees of the forest resources. This transforms the notion of the public trust doctrine where the state has a fiduciary duty to protect natural resources, as in the context of forests the FRA calls for a shift of the responsibility to conserve on local forest dwellers. This shift goes beyond the conventional discourse on citizenship where forest dwelling communities now share the responsibility to protect the environment with the state. This collaborative sharing of responsibilities creates a more dynamic relationship between the environment, citizen and the state. It also transforms the doctrine of eminent domain where forest dwelling communities have ownership rights to forest land which was previously considered as public property belonging to the state and requires the consent of forest dwelling communities for any development project. The insurgency of forest dwelling communities has fundamentally transformed governance and management of forest areas. These rights are not absolute and are limited by use of resources for national interest which come within the ambit of eminent domain.

This transformation through insurgent citizenship from below has permeated into legislative intent as seen in the making of the FRA which was a legislation drafted by the Campaign for Survival and Dignity which was an umbrella campaign speaking to the interests of forest dwelling communities.17 There has thus been a shift from a mere lobby for a new law to enforceable legal rights. This is an interesting process and has shaped environmental citizenship in particular ways where legal processes relating to the environment are transformed from citizen movements from below. Environmental jurisprudence in India has been developed mainly after the procedural innovation of public interest litigation where the expansion of locus standi allows any citizen to bring a case before the court in public interest. Public interest litigation became the dominant tool used by civil society organizations and interested citizens in enabling judicial intervention in the regulation of the environment, so much so that at times they were accused of judicial overreach. The Supreme Court was responsible for the progressive interpretation of Article 21 to include the right to a healthy environment within the ambit of the right to life.18 The reading in of environmental considerations within the fundamental rights was also supported by the incorporation of the public trust doctrine and polluter pays *85 principle as seen in the Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum19 case into environmental jurisprudence in India. Citizen engagement with environmental law occurred through these methods of public interest litigation and indirect participation in the legislative process.

In conclusion, environmental citizenship as derived from the understanding of environmentalism of the poor, refers to three primary values: localized ownership and control of natural resources, participation in decision- making around these resources through free, prior and informed consent and active participation in the conservation efforts of these resources. These values can be traced back to the environmental justice movements led by forest dwelling communities across India which have been discussed earlier. It is these values that are fundamentally altered by the changes proposed by the present Modi government to the existing environmental laws. The present government in its efforts to simplify environmental laws and the environmental clearance process in particular has appropriated the space previously guaranteed to citizens in decision making by shaving away legal provisions that required public participation. This simplification process is reasserting the paradigm of state control of resources which takes away from the decentralized model that environmental struggles have achieved.

III. CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP AND THE ENVIRONMENT

Environmental citizenship thus far as a frame has been explored in the context of forest dwelling communities. I would now like to introduce the notion of corporate citizenship which is a term used to describe the relationship between the corporation and society. Corporate citizenship (CC) has emerged as a prominent term in the management literature dealing with the social role of business.20 This lineage has, most notably, been dominated by the notion of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Carroll21 widely cited CSR model conceptualizes four types of responsibilities for the corporation: (1) the economic responsibility to be profitable; (2) the legal responsibility to abide by the laws of society; (3) the ethical responsibility to do what is right, just, and fair; and (4) the philanthropic responsibility to contribute to various kinds of social, educational, recreational, or cultural purposes. This model has increasingly been incorporating environmental considerations.22 A quick survey of some of the leading extractive companies who operate in India showcases that environmental considerations are emphatically addressed in their statements. Here is a sample of claims of environmental consciousness made by Vedanta as seen through the lens of corporate citizenship.

Vedanta Limited (VL) is a socially responsible corporate that aspires to transform the lives of people surrounding its plant site. VL firmly believes in making the local people a participant in the growth process of the organisation and works as a facilitator of socio-economic transformation of rural parts of Orissa. In accordance with the firm’s social objectives, VL has launched several projects for sustained socio- economic and cultural development of local communities adjoining the plant site. It has launched several projects for sustained socio- economic and cultural development of local communities adjoining the plant site. Mid-day meals for school going children, establishment of Anganwadicentres (pre-schools) and health camps among others have recorded growing success.23

Corporations are recognized as legal persons or having artificial legal personality where they can acquire property and enter into transactions in the market. A frame that I will use to understand the environmental citizenship of corporations is the rights corporations assert over resources in forest areas and their responsibility or obligations to protect the environment. I derive these rights and responsibilities from the existing environmental legal framework.

RIGHTS

RESPONSIBILITIES

Rights to use and harness resources for developmental purposes after gaining environmental clearance from the state.

Responsible to ensure that environmental standards as mentioned within the air pollution, water pollution act and the environment protection act are complied with.

Right to lease forest land for mining purposes

Mine closure plan

What one notices is a gradation in the right to use and the responsibility to conserve. The nature of use and the corresponding standard of conservation vary. In the context of forest dwelling communities what we notice is that sustainable use of forest resources is allowed for collection of firewood, minor forest produce and grazing with the power to determine the working plan of the forest area. In the case of corporations they are vested with the right to exploit resources with the duty to rectify pollution caused by such activities. Prior to earning the right to exploit resources there is a requirement of gaining environmental clearance from the state but most clearances that are granted are conditional. Forest land which are akin to public lands in which the state has the authority to contract natural resources – but the state continues to hold management powers over the area. This of course is now subject to the powers vested with the forest dwelling communities to manage the forest areas under the FRA. Forest land can either be leased for mining purposes or licensed for timber operations else they can be diverted entirely for what has come to be known as non-forest purposes. In the context of corporations entering the forest area in the case of leasing of forest land it can be viewed as a situation where the powers of management are shared with the state as changes to the forest work plan occur with the coming in of such activities. Yet even in the situation of forests being diverted for non-forest purposes, corporations hold considerable power in the management and use of resources. It is this collaborative decision making between corporations and state or regulatory authorities in the management and use of forest resources that creates the framework for the exclusion of forest dwelling communities. This framework of exclusion is where decision making of natural resources is devoid of public participation but is based on the nexus between states and corporations to maximize the capital from the exploitation of resources.

There has been a conscientious attempt to transition from corporate social responsibility to corporate citizenship. It is somewhat hard to make sense *88 of something like “corporate citizenship” from the perspective of rights entitlement, particularly since social and political rights cannot be regarded as an entitlement for a corporation.24 However, Matten and Crane suggest that corporations enter the picture not because they have an entitlement to certain rights, as an individual citizen would, but, rather, as powerful public actors that have a responsibility to respect individual citizen’s rights. In an article by Matten and Crane25 they argue that corporations enter the arena of citizenship in circumstances where traditional governmental actors fail to be the “counterpart” of citizenship. As one element of the group of actors most central to globalization, and indeed one of its principal drivers,26 corporations have tended to partly take over (or are expected to take over) certain functions with regard to the protection, facilitation, and enabling of citizens’ rights formerly an expectation placed solely on governments. We thus contend that “corporations” and “citizenship” come together in modern society at the point where the state ceases to be the only guarantor of citizenship.27 Thus the link between corporations and citizenship is one where the corporation fulfills the vacuum created by the absence of the state or becomes a collaborative guarantor of citizenship rights along with the state. This is a tenuous concept in the context of rights over resources and displacement of local communities. The process of leasing out resources for mining and other extractive activities are seen not only as surrendering resources to private interests but in the absence of independent state actors checking corporate behavior and by corporations acting as collaborative guarantors of citizen rights, it reduces the democratic spaces available to counter corporate interests over resources through state institutions.

Corporate citizenship when described in relation to environmental commitments, takes on two forms which is the voluntary dimension and the obligatory or regulatory dimension. The voluntary dimension is where the corporation exercises its responsibility to set environmental standards for its functioning. This can range from its assurance to reduce adverse impacts from its activities to supporting other environmental initiatives. The obligatory or regulatory dimension refers to the aspect where legal standards set either through statutory legislation or regulatory agencies are mandatory to comply with.28 It is pertinent to make this distinction between the voluntary and obligatory dimension as it sets the foundation for describing the relationship between states and corporations in relation to natural resources. There is an emerging concept that merges the two notions of corporate and environmental citizenship called corporate environmental citizenship. This has been described as “all of the precautions and policies corporations need to take in order to reduce the hazard they give to the environment.”29 This only explains one dimension of what may be referred to corporate environmental citizenship, the other is an aspect peculiar to forest land where they collaboratively manage the resources with the state.

Corporate citizenship, particularly the voluntary dimension, is used to generate an assumption that firms can be trusted to address by themselves any harm their operations cause to the environment. This voluntariness can occur for two reasons – to avoid regulatory scrutiny and as a way of regulatory preemption. Corporations use voluntary standards as a method to showcase the efforts being taken to meet environmental standards which at times are beyond the regulatory requirements. This enthusiasm to move beyond regulatory requirements is seen as a method to justify self-regulation and reduce interference by the state through regulatory scrutiny. The other purpose this voluntary commitment serves is to preempt regulatory or legislative action. To elaborate, this is where corporations struggle to maintain environmental standards in the realm of voluntary commitments rather than allowing it to enter the formal legal requirements, it is the struggle to assert self-regulation of activities as opposed to state interference or interference by forest dwelling communities. Though this motivation of corporate citizenship is grounded on the role of the state as a policeman as Gramsci describes. If the state is seen as the enforcer of regulatory standards then the relationship between the state and corporations will be antagonistic. This however is not the case as states often collude with corporations to maximize the benefits from the exploitation of natural resources. Steve Tombs in his paper30 on state-corporate symbiosis speaks about the state as a capitalist state where state decision-making is to *90 create favourable conditions for the reproduction of capital within its boundaries. While this is a simplistic expression of the nuances of capitalist state, it acts as a window to understand the basis for the nexus between corporations and state bodies. In the same paper Tombs describes corporations as institutions that are created for the mobilization, utilization and protection of capital. Corporations, Tombs explains, are a recent historical phenomenon as wholly artificial entities whose very existence is provided for, and maintained through the state via legal institutions and instruments. It is almost as if the existence of the state is a necessary condition but not a sufficient one, as corporate citizenship is being seen as a manner in which corporations can act as guarantors of citizen rights to individuals.31

The relationship between corporations and states in forest areas is one of nexus where the capitalist state works with the corporate enterprise to maximize profits from harnessing natural resources. The role of the state as a policeman through regulatory agencies is only realized when forest dwelling communities bring these violations and nexuses to the attention of the judiciary or through protest. It is this functional role that forest dwelling communities have played since the colonial era in protecting India’s forests. This nexus between corporations and states in forest areas are realized through state failure to put in place effective legal regimes, enforce existing laws adequately or respond effectively to violations. This state failure around law and regulation has been checked by forest dwelling communities when viewed historically through the environmental justice movements. Thus corporations in some ways exist both inside and outside the state and at times take over state function of either regulation or legislation through voluntary environmental commitments. An idea that captures this nexus has come to be known as ‘state-corporate crime’ which has been described as illegal or socially injurious actions that occur when one or more institutions of political governance pursues a goal in direct co-operation with one or more institutions of economic production and distribution. This understanding puts forth that the state in its efforts to realize its capitalistic requirements should not collude with corporations in the absence of adequate representation of other interests. Tombs in his article states that the role of the state as regulating contradictory class practices to maintain and restore equilibrium is needed.32 The state becomes the site of negotiation between these diverse and multiple interests but the prioritization of corporate interests is what makes this nexus problematic. The provisions within the existing environmental law framework that allow for avenues to challenge this nexus are the ones that are being subverted by the proposed changes that the present government is putting forth. What we are witnessing is a transition from the state as a regulator to self-regulation by corporations through the notion of corporate citizenship.

This departure from environmental citizenship to corporate citizenship was done to highlight the relationship between corporations, citizenship and the environment. When environmental considerations are brought into this milieu what one sees is the articulation of corporate responsibility to voluntary environmental objectives and the mandatory compliance with existing environmental laws.

Recent reports suggest that despite the stringent environmental standards imposed by existing laws, non-compliance by industries remains an issue in different sectors. This occurs because there is a lack of enforcement by the state agencies to protect natural resources. Further, corporations are only held accountable, and mostly by civil society organisations, for non-compliance after damage have occurred. The time-consuming court system also increases the adverse impact on the environment.33 Tombs concludes his article on a critical note about this nexus where he declares that corporations engage in illegality at the prompting of or with the approval of the state authorities or they fail to respond to such illegalities. In the changes proposed in the TSR Subramanian committee report where corporations will gain their environmental clearance through a self-certification process by disclosing the project plan and its ability to pollute, it straddles this path between voluntary and formal legal commitments. The corporations are trusted to reveal the impact of their project and suggest solutions which can be viewed as voluntary and they receive formal legal recognition upon the granting of clearance. This poses a peculiar scenario where the state as opposed to being the regulator and standard setter accepts the standards offered by the corporations.*92

IV. INTER-RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP AND CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP

As discussed above while environmental citizenship aims to assert the powers of local communities over resources, corporate citizenship attempts to exploit natural resources with the support of the state machinery. The inter- relationship between these two forms of citizenship which are being asserted simultaneously is one of struggle expressed through legal and political challenges. The present environmental legal framework allows for such a challenge as it allows for corporate citizenship’s control over natural resources to be challenged by local communities using provisions of the FRA and EIA processes. This challenge results in the prioritization of one form of citizenship over the other. Going back to the Vedanta judgement where the gram sabhas were asked to provide consent for the entrance of the bauxite mine, it was the prioritization of local communities rights over resources in relation to the corporate claims over it. While in the case of Chattisgarh, Jharkhand and Karnataka illegal mining continues despite it being legally challenged, these are instances where corporate citizenship and control over resources eliminates the tenets of environmental citizenship. This prioritization is based on the different environmental politics prevailing yet there is increased suppression of environmental citizenship claims to resources and the strengthening of corporate citizenship with the support of the state machinery.

The recent changes proposed to the environmental laws by the present government eliminate any legal avenue for corporate citizenship to be challenged. It does so by shaving away rights of local communities over their resources and public participation in the decision-making of around these resources. In the section below I discuss the proposed changes and their impact on the tenets of environmental citizenship as derived from the environmental justice movements in India.

V. CHANGES IN THE ENVIRONMENTAL LEGAL FRAMEWORK

There has been a drastic shift in the environmental legal framework since the coming in of the present government. The changes have been at different levels but the particular changes that I would like to focus on are:

1. The idea of utmost good faith as proposed in the TSR Subramaniam report;*93

2. The land acquisition ordinance with focus on the changes in the consent provisions;

3. Dilutions of the FRA since late 2014; and

4. The crack down on environmental organizations and the arrest of Priya Pillai, a senior campaigner with Greenpeace.

I chose to focus on these particular changes because they illustrate how the tenets of environmental citizenship of forest dwelling communities are being altered. The tenets of environmental citizenship that I would like to focus on are participation in environmental decision making and control over the use and management of forest resources.

Principle of Utmost Good Faith in the TSR Subramanian Report

The TSR Subramanian committee was set up on August 2014 with the mandate to amend five key environmental statutes namely the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 , Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980, Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, Air (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1974 and the Water (Prevention and Control of Pollution) Act, 1981. The committee submitted its report on November, 2014. The committee went on to make a host of recommendations but the particular recommendation that I would like to examine is the principle of utmost good faith borrowed from Insurance law. In Chapter 8 of the report by the High Level Committee they propose a new legislation called the Environmental Laws (Management) Act. The objective of the proposed new law is to act as an umbrella law which will also provide the legal architecture for a ‘single window’ environmental clearance process. In the summary of the legal mechanisms of the proposed new law the report reads as follows:

Drawing inspiration from this concept under the insurance law and to meet the desirability of a ‘single window’, the committee being alive to the legal position that the lacunae noted could not be addressed through executive orders, has decided to recommend the following course of action:

(i) Parliament to enact a law that would constitute ‘National Environment Management Authority’ (NEMA) at the Centre and ‘State Environment Changing Terrain of Environmental Citizenship in India’s Forests *94 Management Authority’ (SEMA) in states – both comprising experts in the different fields – which will deal with applications for clearances and permissions under environment related laws at the Central and State level respectively – thus a single window.

(ii) The new law – Environmental Laws (Management) Act (ELMA) would oblige an applicant to disclose everything about his proposed project, especially its possible potential to pollute and the proposed solution thereto- in short all that would be relevant to making a decision on granting or refusing the clearance applied for. The proponent and the experts who support his case will be required by law to certify that ‘the facts stated are true and that no information that would be relevant to the clearance has been concealed or suppressed’.

(iii) On the basis of this application and certifications, the matter will be examined either by the Central authority NEMA or the state level authority SEMA – depending on the category of the project as notified. The inspector, as a rule, has limited role to play in the proposed clearance process – in any given case the option of site inspection at any time is always reserved to the authorities. In respect of recommendations of NEMA for grant of clearance or rejection, the final decision will be by the Central Government.

(iv) Introducing the concept of ‘utmost goodfaith’, if at any time after the application is received – even after the project takes off – it is discovered that the proponent had in fact concealed some vital information or had given wrong information or that the certificates issued by the experts suffer from similar defects, severe *95 consequences will follow under the new Act ELMA; and they include heavy fine, penalties including imprisonment and revocation of the clearance, – and in serious cases arrest of the polluter. 34

As seen in the four part process proposed for granting environmental clearance there is increased reliance on the information to be provided by the project proponent about the potential environmental impact of the project. This process of placing the information before the state and national environmental management authorities to make the decision does not mention the element of consent or consideration of the project affected communities. The only check and balance of whether the information provided by the proponent is authentic is the principle of utmost good faith. There is initial trust that the project proponent will be transparent in the declaration of the information. However, in the event of wrong information or an act of concealing information, he will subject to fines and penalties. The principle of utmost good faith only extends to the question of environmental impact, the question of communities to be impacted by the project is completely sidelined. The public hearing process does not feature in the decision making process of granting environmental clearance. The forest dwelling communities more vulnerable to the impacts from industrial projects do not feature in the proposed decision making process for granting environmental clearances. Though the recommendations of the High Level Committee went on to be rejected by the parliamentary standing committee, the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change introduced the Environmental Laws (Amendment) Bill in August, 2015 to amend the Environment Protection Act, 1986. It was open for public comment in October, 2015. The amendments continue to push for a bureaucratization of environmental governance and include elements of the principle of utmost good faith where companies are penalized for non-compliance of environmental standards set at the time of granting the clearance.*96

Introduction of the Land Ordinance and its Impact on the Consent Provision

The new government introduced amendments to the existing Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013 (‘LARR’) through an ordinance in 2014. Since the earlier act was protested as being restrictive by industrial bodies; the ordinance was seen as a means to bring about some flexibility into the procedure. The particular aspects of the procedure which were viewed as hurdles was Sec 2(2)(b)(1) and (2) of the Act which requires consent of at least 80% of the affected families for private companies and about 70% in the case of public-private partnerships. The ordinance excludes a range of more projects whether in the public or private sector from the condition of getting consent from affected families. Projects to be excluded include all those relating to defence production, power projects and other projects for rural infrastructure, housing for poor, industrial corridors and PPP projects. Since most of land acquisition has been for such power and irrigation related projects, the exemption given from getting the consent will be disastrous for the farmers.35

This exclusion of consent can be seen as an effort to reinforce the powers that flow to the State from the doctrine of eminent domain. This is similar to the efforts being made to dilute the public hearing aspect of the environmental clearance process. Though in August, 2015 the ordinance was allowed to lapse after protests spread across the country in opposition to the ordinance. Given than decisions relating to land acquisition is a state subject, different states are now leading the effort to amend provisions of the LARR. Tamil Nadu, for instance, has amended the Act proposed by the Center by inserting a new Section 105 where land acquisition for industrial purposes and highways will be exempt from the provisions of the Act. The LARR had taken a progressive step of incorporating provisions which required gram sabha consent for land acquisition which should have remained as it protected the rights of communities impacted by such acquisition.*97

Dilution of the FRA, 2006

The FRA was a landmark legislation that aimed at correcting the historical injustice experienced by forest dwelling communities. The Act was a product of a unique political struggle under the banner of the Campaign for Survival and Dignity. The Act identifies thirteen rights under Section 3 which guarantee the forest dwelling communities with ownership of forest land as well as rights to use and control the resources within the forest areas. The Ministry of Environment and Forests in 2009 made it mandatory that the consent of the gram sabha be obtained for industrial projects before applying for permission to the Ministry of Environment and Forests. The then UPA government tried to withdraw this order but the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the FRA in the Niyamgiri judgement where the consent of the 12 gram Sabha’s was required before the beginning of the mining operations made it difficult.36 The FRA in many ways became a law that fundamentally challenged the authority of the state in forest areas by legally reinstating the historical right of ownership and control of forest dwelling communities. This law was notoriously categorized as a hurdle for development as forest rights of forest dwelling communities had to be settled before any clearance process could begin and further the consent of the forest dwelling communities was needed.

The present government in its desire to relax the procedure for private companies and governments to gain access to resources has been attempting to dilute the FRA. This became evident when the Maharashtra forest department issued the Maharashtra Village Forest Rules, 2014 where the forest department has regained control of trade in forest resources and management despite the FRA which rests these rights in the local community. This was seen as an attempt by the forest department to regain control in the decision-making around forest areas. The Ministry of Tribal Affairs under Jual Oram challenged the interpretation of the FRA that the forest department continued to have rights of management and control over trade of forest produce but under pressure from the Ministry of Environment and Ministry of Transport he was asked to withdraw this directive.37*98

This comes against the backdrop of the challenge to consent provisions in late 2014. The Business Standard reported that the different ministries including environment, tribal affairs and law met under the directive of the Prime Minister’s Office to systematically do away with the consent requirement and replace it with a requirement of mere consultation with forest dwelling communities.38 In an unprecedented move the Government of Chhattisgarh in 2016 cancelled the rights of forest dwelling communities in parts of Surguja district to facilitate a coal mining project.39 This is another instance where consent provisions were viewed as a hurdle to development, rather than a democratic means for discussion.

Cracking down on Environmental Organizations and Activists

On January 11, 2015 Priya Pillai a senior campaigner from Greenpeace was prevented from flying to London where she was to present before British legislators the human rights violations experienced by local communities in Mahan, Madhya Pradesh.40 This restriction was because she among many other environmental activists were placed on a look out notice and were being labelled as disrupting India’s economic activities. This incident was immediately followed by freezing Greenpeace’s accounts on the grounds that they were violating the Foreign Contributions Regulatory Act, 2010 (FCRA).41 The Delhi High Court in January, 2015 ruled in favour of Greenpeace, allowing the usage of foreign funds since they were not indulging in any ‘anti-national’ activity. Despite this victory the FCRA has been used as a political tool to shut down many civil society organizations, particularly those working on environmental issues. This particular use of the FCRA needs to be read with the other changes that have *99 been highlighted in the paper. Civil society organizations are an essential layer in the assertion of environmental citizenship where they hold governments and corporations accountable to human rights and environmental violations through on the ground campaigns to legal activism. To reduce them to mere anti-national elements is another instance of the shrinking democratic space in environmental politics in India.

VI. ANALYSIS OF THESE CHANGES AND ITS IMPACT ON ENVIRONMENTAL CITIZENSHIP IN INDIA

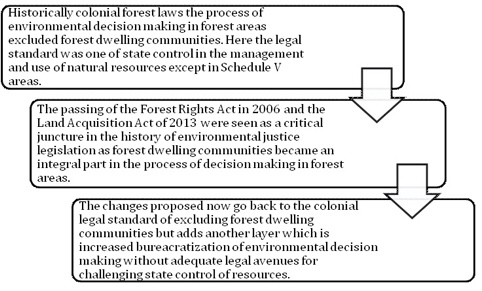

Transitioning back to Colonial Standards of Forest Management

These changes can be seen as creating a shift in the legal standards for decision-making around environmental issues. It can also be viewed as a process of degenerating the rights of forest dwelling communities by bureaucratizing environmental governance. In the figure below I elaborate on the shift in legal standards which will lay the foundation of the impact of these changes on environmental citizenship.

*100

In the figure above the shift in the legal standard is regressive which undoes the steps taken with the passing of the FRA in 2006. The greater impact though is in the sensibility of environmental citizenship that has come to be embedded in the struggles of forest dwelling communities after the passing of the FRA where the claims being made by the movement had gained the shelter of law. This process of rights degeneration and delegitimization of their participation in the management and control of forest areas places them in a precarious position which existed prior to the FRA. This process of rights degeneration also results in reinforcing the historical injustice faced by forest dwelling communities. This only strains the relationship between forest dwelling communities and the state authorities as their recognized rights of free, prior and informed consent are not respected. The insurgent citizenship which was an essential element which opened up spaces within environmental law for forest dwelling communities to actively participate is now transitioning back to the colonial standard of exclusionary conservation. Through the denial of the right to participation in environmental decision making within forest areas the nexus between state authorities and corporations will remain unchallenged through legal processes. It will delegitimize the rights of management and control vested with forest dwelling communities to reinstating the forest department as state agency responsible for governing the forests. This is problematic in many ways but fundamentally this exclusionary form of conservation will risk the opening up of India’s forests to large scale mining.

Conflict and Environmental Citizenship

Environmental citizenship in India is a product of conflict between competing interests over natural resources. The forest areas where such conflicts have played out through history have shown that it has a transformative influence over the law and state functions in these areas. The conflicts over ownership, control and management over forestland resulted in the political struggle which eventually led to the passing of the FRA. The current changes proposed seek to avoid conflict by quelling participation and dissent through shrinking the legal avenues where forest dwelling communities could represent their interests. It can be argued that law is both a maker of hegemony and a means of resistance. The ability of environmental law to accommodate resistance is reduced and instead resistance to the use of forest resources has to operate outside the realm of law. This inability of environmental law to accommodate multiple interests has rendered the law primarily as an instrument *101 of hegemony where the decisions of state and private enterprises are prioritized and legitimized. Environmental law is being pushed to enable the expropriation of resources and resistance is being managed as issues of maintenance of ‘law and order’.42 The framework of environmental law in India – where resistance was allowed to be expressed in the decision making through provisions seeking consent of the impacted community within the FRA and the LARR are now seen as unnecessary and burdensome. The language configures the motivation for the amendments to which is to streamline or make the process simpler to comply. This exercise of simplification is seeing the development of a process where local consent is not undertaken as it makes the process more complex and prolonged. In an effort to streamline the decision making around forest areas I believe that we are seeing the rise of what I refer to as an environmentalism of convenience. An environmentalism of convenience is where compliance to environmental laws is made easy and simple. Where ease of compliance is prioritized over addressing the difficult questions of consent and impact on local populations.

Amita Baviskar in her article about the cultural politics of nature, highlights that absence of conflict does not necessarily indicate harmony but ‘symbolic violence’ when relations of domination are transfigured into affective relations which begin to operate.43 The role of law in creating the façade of harmony is achieved by reducing legally recognized conflicts or conflicts that have a basis in a legal claim as seen here by degenerating the rights of forest dwelling communities. This will only result in the making of social relations that gain power and legitimacy through this convenient legal arrangement. Conflict accommodated within the contours of law will ensure that rights over resources are adequately negotiated. This de-recognition of the conflict that emerges from forest dwelling communities within the law will only push for resistance being seen as communities taking law into their own hands. This resistance then is seen by the law in multiple forms either as sedition or disrupting public order. This environmentalism of convenience has rendered the participation of forest dwelling communities and their rights over forest areas as inconvenient and cumbersome.*102

VII. CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP BEING STRENGTHENED

Corporate citizenship as described earlier as a notion gets strengthened through the concept of utmost good faith. The state vests complete trust in the corporation to reveal the damage that its activities will cause to the environment. This is a push towards the voluntary dimension of corporate citizenship where the corporations begin to self-regulate. The state intervenes only when there is misinformation or omission about the potential environmental damage. This is a peculiar system where the state lets go of its role as a regulator but only interferes with the clearance process at the time of certification. This reduced role of the state and increased trust in corporations to self-regulate only reaffirms the understanding of corporate citizenship. The reduced role of the state also paves the way for corporations to fill in the pockets where the state is absentee for instance in the granting of citizenship rights to individuals. It increases the power of corporations to manage natural resources provided they reveal the nature and extent of the damage that will be caused. This will protect them from regulatory scrutiny and they begin to duplicate the functions of state authorities around resources.

The state-corporation nexus as discussed earlier will be strengthened as the role of the state from a regulatory state to a capitalist state is enabled through the increased trust for corporations to manage environmental standards. In some instances self-regulation is seen as way to address red-tapism yet whether this may result in lower environmental standards is yet to be seen. The level of decision-making around forest resources is restricted to the state and corporate entity. This frame coupled with reduced participation has drastically changed the nature of environmental citizenship. Beyond the power to self-regulate corporate citizenship has strengthened with the idea of compensatory afforestation making its way back into the forest management strategies. Compensatory afforestation calls for afforestation in exchange for the damage done to the forest resources. This method only enables corporations to take control of forests and replace it with another area allocated for afforestation where forest dwelling communities do not have claims to forest resources. These factors are strengthening the notion of corporate citizenship in India’s forests.*103

VIII. INCREASING THE BURDEN ON THE JUDICIARY

The coming together of reduced participation of forest dwelling communities in the governance process as well as increased self-regulation capacity of the corporations results in courts and the National Green Tribunal (NGT) as an avenue for negotiating environmental conflicts. Public interest litigation will be seen as an active tool in addressing grievances of forest dwelling communities. This only pushes conflict from the arena of local governance structures to the judiciary. This will increase the burden on the courts and the NGT in resolving environmental disputes. The power in incorporating these grievances within the decision-making around the use of forestland was to ensure that communities articulated their decisions without having to go through the tedious process of filing cases. This will adversely impact the forest dwelling communities in accessing justice as approaching courts and the NGT are both cost intensive and time consuming. The advantage of incorporating the grievances in the decision making early on is that it impacts the ongoing decision about the diversion of forest land whereas in the case of courts it may take longer and considerable environmental and human rights violations may have already taken place.

The judiciary and the NGT have already having played an important role in the shaping of environmental jurisprudence and our understanding of environmental citizenship through landmark cases. Yet this increased reliance on courts by reducing other legal avenues can be tricky as local communities impacted by a development project will invest all their resources in courts without a guarantee of a potential win though such cases may stall the projects continuation.

IX. CONCLUSION

The shift in environmental citizenship has occurred within the law though not extending to the language of resistance which will now be forced to function outside the blanket of law. India had positioned itself in a unique space where environmental justice claims were explicitly part of the legal framework, this shift can be seen as the creation of the inconvenient environmental citizen who will always be outside the ambit of the law. The model of environmental citizenship highlighted earlier now sees a change where they do not form an Changing Terrain of Environmental Citizenship in India’s Forests *104 integral part of the decision making process around environmental issues but begin to be viewed as a hurdle in the realization of different economic activities. In the movie ‘Dweepa’ the protagonist who refuses to leave his village is seen drowning in his traditional clothes at the altar of the sacred temple. Whether this process of rights degeneration will result in violent and tragic consequences for forest dwelling communities is yet to be seen as these legal amendments fundamentally change the legal environmental citizen to an inconvenient hurdle.

12(2) Soc. L. Rev. 74 (2016)

1.

Arpitha Kodiveri graduated with a degree in law from ILS Law College, Pune with a keen interest in environmental law.Upon graduating she was awarded the Young India Fellowship and then went on to work as an environmental lawyer with Natural Justice where she supported forest dwelling communities in Rajasthan and Gujarat in their struggles to assert their rights over resources. She recently graduated with an LL.M in environmental law from UC Berkeley School of Law as a Fulbright-Nehru scholar and presently works as a senior research associate in the forest and governance program at the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment in Bangalore.

2.

Ramchandra Guha, Radical American Environmentalism: A Third World Critique, 11 ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS 71-83 (1989).

3.

Id.

4.

An armed left-wing movement that began in 1967.

5.

In this context I am not referring to the State as an abstraction of the particularities of the center, state and local governments.

6.

Referring to the power of the state to acquire land for public purpose as defined under Section 2 (1) of the Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement Act, 2013.

7.

Public trust doctrine is understood as the responsibility of the state to conserve resources which they hold in trust on behalf of the citizens.

8.

M.C Mehta v. Kamal Nath, (1997) 1 SCC 388 1996 Indlaw SC 1476 (Supreme Court of India).

9.

Kanchi Kohli & Manju Menon, ELEVEN YEARS OF THE ENVIRONMENT IMPACT ASSESSMENT NOTIFICATION, 1994- HOW EFFECTIVE HAS IT BEEN? (May 2005).

10.

Ben Orloveet al., Contemporary Debates on Ecology, Society, and Culture in Latin America, 46 LATIN AMERICAN RESEARCH REVIEW, 115-140 (2011).

11.

Alex Latta & Hannah Wittman, Environment and Citizen in Latin America A New Paradigm for Theory and Practice, 89 EUROPEAN REVIEW OF LATIN AMERICAN AND CARIBBEAN STUDIES 107-116 (October 2010).

12.

D. Béland and R. Hansen, Reforming the French welfare state: solidarity, social exclusion and the three crises of citizenship, 23(1) WEST EUROPEAN POLITICS, 47-64 (2000).

13.

James Holston, INSURGENT CITIZENSHIP: DISJUNCTIONS OF DEMOCRACY AND MODERNITY IN BRAZIL (2008).

14.

Samatha v. State Of Andhra Pradesh 1997 Indlaw SC 3331, Appeal (civil) 4601-02 of 1997 (Supreme Court of India).

15.

Orissa Mining Corporation v. Union of India, 2013 (6) SCALE 57 2013 Indlaw SC 255 (Supreme Court of India).

16.

Kaustav De, Gaonchodabnahi (we will not leave out village), YOUTUBE (March 28, 2009) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8M5aeMpzOLU.

17.

M Rajshekhar, The Act that Disagreed with its Preamble: The Drafting of the “Scheduled Tribes and Other Traditional Forest Dwellers (Recognition of Forest Rights) Act, 2006, (2012) (unpublished paper) (on file with author).

18.

Subhash Kumar v. State of Bihar, AIR 1991 SC 420 1991 Indlaw SC 913.

19.

Vellore Citizens Welfare Forum v. Union of India and others, AIR 1996 SC 2715 1996 Indlaw SC 1075 (Supreme Court of India).

20.

Dirk Matten & Andrew Crane, Corporate Citizenship: Toward an Extended Theoretical Conceptualization, 30(1) THE ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW, 166-179 (Jan., 2005).

21.

Archie B. Carroll, A Three-dimensional conceptual model of corporate performance, 4(4) THE ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW, 497-505 (October, 1979).

22.

Þükrü Özen & Fatma Küskü, Corporate Environmental Citizenship Variation in Developing Countries: An Institutional Framework, 89(2) JOURNAL OF BUSINESS ETHICS, 297-313 (Oct., 2009).

23.

Aim & Vision, VEDANTA, http://www.vedantaaluminium.com/csr-aim.htm(last visited July 10, 2016).

24.

D.J. Wood & J.M. Logsdon, Theorising business citizenship, in PERSPECTIVES ON CORPORATE CITIZENSHIP: 83-103 (J. Andriof & M. Mclntosh eds., 2001).

25.

Matten & Crane, supra note 19.

26.

J.A. Scholte, GLOBALIZATION; A CRITICAL INTRODUCTION (2000).

27.

Matten & Crane, supra note 19.

28.

Özen & Küskü, supra note 21.

29.

Özen & Küskü, supra note 21.

30.

Steve Tombs, State-Corporate Symbiosis in the production of Crime and Harm, 1(2) STATE CRIME JOURNAL 170-195 (Autumn 2012).

31.

Id.

32.

Tombs, supra note 29.

33.

Environmental Compliance and Enforcement in India: Rapid Assessment, available at https://www.oecd.org/env/outreach/37838061.pdf (last visited April 20, 2016).

34.

Report by the High Level Committee to Review Various Acts Administered by Ministry of Environment, Forest & Climate Change, Government of India (November 2014) available at http://envfor.nic.in/sites/default/files/press-releases/Final_Report_of_HLC.pdf (last visited April 20, 2016).

35.

Based on the amendments proposed in The Right to Fair Compensation and Transparency in Land Acquisition, Rehabilitation and Resettlement (Amendment) Ordinance, 2015 available at http://www.prsindia.org/uploads/media/Land%20and%20R%20and%20R/ larr%202nd%20ordinance.pdf (last visited July 12, 2016).

36.

Orissa Mining Corporation Ltd. vs Ministry Of Environment & Forest, WRIT PETITION (CIVIL) NO. 180 of 2011 (Supreme Court of India).

37.

Shruti Agarwal, Tribal Affairs Ministry Gives into Pressure and ‘okays’ village forest rules (January, 2016) available at http://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/tribal-affairs-ministry-gives-in-to- pressure-okays-village-forest-rules-52402 (last visited April 18, 2016).

38.

Nitin Sethi, Taking away forests: Tribal consent regulations to be diluted, BUSINESS STANDARD (October 2014) available at http://www.business-standard.com/article/economy- policy/taking-away-forests-tribal-consent-regulations-to-be-diluted-114103100022_1.html (last visited April 22, 2016).

39.

Nitin Sethi, Chhattisgarh government cancels tribal rights over forest lands, BUSINESS STANDARD (February, 2016) available at http://www.business-standard.com/article/current-affairs/ chhattisgarh-govt-cancels-tribal-rights-over-forest-lands-116021601327_1.html (last visited April 22, 2016).

40.

Meena Menon, Greenpeace campaigner Priya Pillai offloaded at airport, THE HINDU (January 11, 2015) available at http://www.thehindu.com/news/national/greenpeace-campaigner-priya- pillai-offloaded-at-airport/article6777773.ece (last visited April 22, 2016).

41.

Jason Burke, Greenpeace bank accounts frozen by the Indian Government (April, 2015) available at http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/apr/10/greenpeace-bank-accounts-frozen-by- indian-government (last visited April 18, 2016).

42.

Nandini Sundar, Laws, Policies and Practices in Jharkhand, 40(41) ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY 4459-4462 (Oct. 8-14, 2005).

43.

Amita Baviskar, For a Cultural Politics of Natural Resources, 38(48) ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL WEEKLY 5051-5055 (Nov. 29 – Dec. 5, 2003).